Though the price of wheat may entice hog producers to add the small grain to swine diets, Kansas State’s Mike Tokach urges producers to tread carefully, heeding precautions.

Feeding pigs to get them to market is the main objective for hog producers. Doing it as economically and efficiently as possible is integral to managing that objective.

Feed costs make up a good portion of producers’ inputs, so it may be enticing to look at ways to lessen the dollar signs that go along with that cost. Right now, the price of wheat, mainly in relation to the price of corn, has some producers looking at the small grain as an alternative feedstuff to fill hogs’ bellies. Kansas State University’s Mike Tokach says adding wheat to swine diets is nothing new for Kansas hog producers, but there are necessary precautions to be heeded.

“One of the issues with wheat is with grinding and handling on the mill side,” says Tokach, who specializes in swine nutrition for KSU Extension. Grinding and handling concerns arise at farm or commercial feed mills if they are not accustomed to grinding multiple grains at the same time. Tokach says some mills are “set up to do that fairly easily, while others are not at all.”

He says Kansas producers who mill their own grain and wish to switch between using multiple grains have to be able to handle large-enough quantities of grain to make it worth their effort to go through all the changes that need to take place.

Wheat needs to be ground relatively fine, but it does have a tendency to “flour” more easily than corn does, meaning you get a lot of “really fine” particles, and “when that happens, that wheat can cause ulcers more easily than with what we see with some of the other ingredients, so you do have be careful with particle size.” In addition to ground wheat particle size potentially leading to ulcers in pigs, particle size also can cause flowability issues in feed lines and bins, potentially leading to out-of-feed events “that can also lead to ulcers that occur when pigs don’t have access to feed for a period of time,” he says.

Tokach recommends grinding wheat to the 500- to 700-micron range, taking into consideration the producer’s feeding system and how the grain is being used.

“If they’re feeding 100% of the grain and have smaller feed lines, they have to end up having it just a little bit bigger in particle size,” he says. “If they have a 3-inch or larger line or they’re mixing it into a corn-soybean diet, or a diet with other ingredients that help with flowability, then they can use a smaller particle size and get better feed efficiency.”

Most producers in Kansas are using wheat as a partial replacement for corn in the diet, and Tokach suggests that any producer contemplating adding an alternative feedstuff to the diet take it slow. “If you haven’t used it before, stepping your way slowly into it or using a lower level until you reach your comfort level is helpful to see about its flowability and the grinding.

“We know with good-quality wheat, we can replace all of the corn in the diet, and a lot of the soybean meal,” Tokach says.

When the quality of wheat does come into question, Bob Thaler, South Dakota State University Extension swine specialist, suggests precautions need to be taken so as not to jeopardize your hog herd’s health.

Conditions this growing season appear to be right for fusarium head blight (or scab) growth in South Dakota. This blight leads to the production of the mycotoxin deoxynivalenol (DON) in wheat.

Thaler says that DON-contaminated grains can cause problems for livestock, but pork producers have several options when dealing with this situation.

DON does not cause health or reproductive problems in swine, but when the total concentration in the diet reaches above 1 ppm, pigs will eat less feed, or in some cases, simply vomit and then quit eating completely, clarifying the reason DON is also commonly known as “vomitoxin.”

This decrease in feed intake will result in slower gains but not death. There are some commercial products available that bind the mycotoxin aflatoxin, but they are not effective in completely alleviating the effects of DON.

Therefore, if a producer wants to use DON-contaminated grain, Thaler recommends blending the tainted wheat with “clean” grain to keep those levels in the complete feed below 1 ppm. For example, if the wheat contains 2 ppm DON and it is included in the diet at 25% of the total ration, the final diet should only contain 0.5 ppm DON if the other ingredients are clean. At this level, pig performance will not be affected.

Obviously, this will only work if a producer knows exactly what he or she is working with. Thus, Thaler says it is essential to know how much mycotoxin is in the grain by taking samples from several locations in the bin or load, and sending them to a certified lab for analysis. He stresses more is better than less when submitting samples, because mold growth varies throughout the field and also between fields, and more samples will present a “better idea of the actual levels of DON you’re dealing with.”

With sample results back, producers can then blend the contaminated grain with clean grain to keep the diet’s mycotoxin level below 1 ppm. Thaler also recommends strategically feeding the moldy grain, feeding it to finishing pigs and cull sows, but keeping it out of gestation, lactation and nursery diets. Mold inhibitors can be added to prevent further mold growth, but inhibitors will not reduce or eliminate the mycotoxins already present.

Mycotoxins can appear in corn, but wheat seems to be more susceptible — and that seems to be a regional issue, with drought during the growing season or moisture at harvest time lending to mycotoxins becoming a wheat issue, Tokach says. Hail damage can also open corn and wheat up to mycotoxin issues, so producers need to be aware of their feed source.

Tokach says another problem is some of this year’s wheat crop has been lower in crude protein than what producers traditionally had become used to, “so it doesn’t replace as much of the soybean meal, so you have to use it more carefully in the formulation.”

Hogs adapt easily

Changing up rations is not a big deal for pigs, as Tokach says hogs adapt more easily to a change in diet than cattle. “But you don’t want to keep switching on a real frequent basis. Feeding trials tell us that if the diet doesn’t cause flowability issues, so you keep feed in front of the animal, pigs switch relatively easily between diets,” he says. “Now it’s another thing with the heat stress that we’ve seen in much of the Midwest. You wouldn’t want to make a huge diet change when you already have other things compromising intake.”

The same goes for a disease outbreak in the herd. It would be best to hold off on a diet change, “but if you’ve got healthy pigs growing well and it’s a cool time of year, you shouldn’t see any effect of switching back and forth between ingredients, as long as you have palatable ingredients to start with.”

Tokach reiterated that “you’d want to be more careful [switching feed rations and feeding tainted grain] with lactating sows and early diets for nursery pigs. Those stages of production are a lot more sensitive to negative impacts on feed intake, so you do want to be a lot more careful there.”

DON issues

Some pockets of Kansas had issues with fusarium mycotoxins showing up in last year’s corn harvest. “As the corn comes out of storage, some people are looking for other ingredients to blend into their diets to lower the potential contamination issue,” he says.

Type of toxins in grains fed to pigs determines the effect the feed will have on the animal — from the pigs simply not eating to getting sick if they do eat the feed. “When you first put a feed in front of them, and this goes for fumonisins, or aflatoxin, or with DON or vomitoxin if in high enough levels that it is very noticeable to pigs, they will reduce feed intake almost immediately,” he says. Feed intake will be compromised for the first three to seven days; then they actually get a little bit adjusted, and feed intake will improve, but not back to levels before the mycotoxin was introduced. “Once you remove the mycotoxin, feed intake will normally go back up to normal, but it will depend on the mycotoxin and how much got stored in their body and how long it takes them to detoxify their body and get rid of the mycotoxin.”

It is not 100% known if the taste or smell turns hogs away from the mycotoxin-tainted feed, but Tokach says the younger pigs and the lactating sows will turn away almost immediately. Trials with vomitoxin show that “they back off within that first day in consumption, and by Day 3 they may only eat 25% of what they normally eat, but then they start eating much higher levels very quickly, and by seven days they won’t be completely back to normal, but they’ll be close — it’s almost like they get to the point of realizing that there isn’t going to be anything else there, so they’re going to have to eat it.”

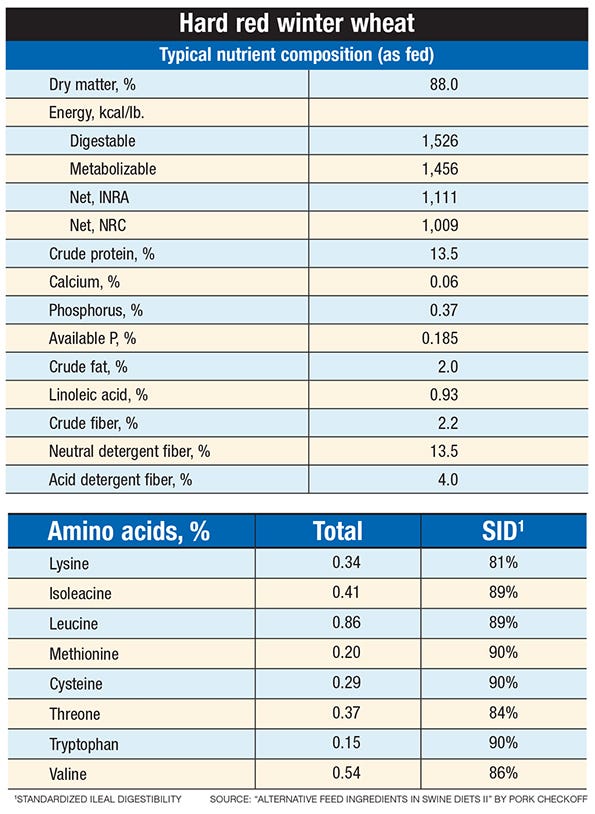

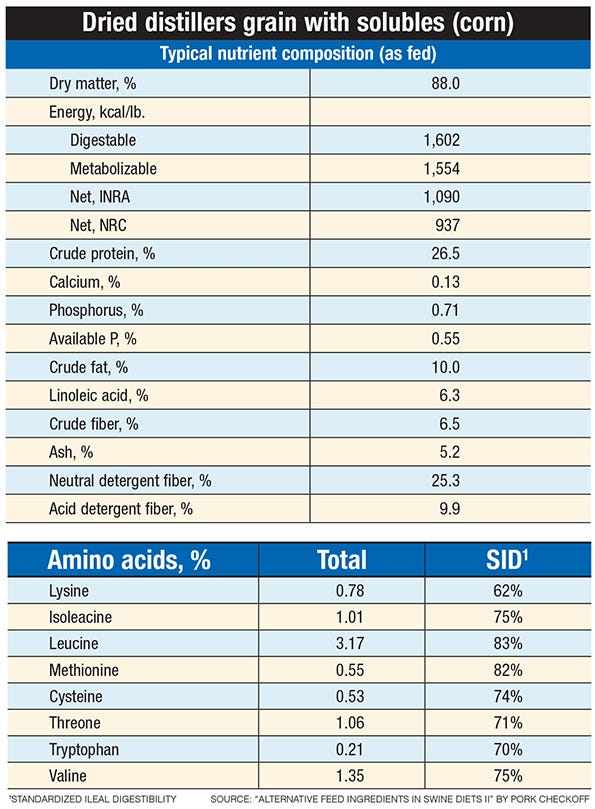

Tokach collaborated with other researchers to create “Alternative Feed Ingredients in Swine Diets II: Use, Advantages and Disadvantages of Common Alternative Feedstuffs” for the pork checkoff in 2008. Though this report may be dated, Tokach says most of the information for the ingredients remains valid, with the exception of dried distillers grain with solubles as oil contents fluctuate as ethanol plants have increased the amount of oil removed in the milling process.

High sulphur levels

Speaking of feeding DDGS, Tokach acknowledges the high sulphur levels in DDGS, and the potential link to higher levels of hydrogen sulfide created in the manure pits. “We know it increases the amount of sulphur that’s exiting the pigs in the feces and urine, so that is a concern. … We can overcome some of that by diet formulation. We use higher levels of synthetic lysine when we feed DDGS, and that lowers the levels of sulphur amino acids, so you can overcome a lot of that negative impact.”

Tokach cautions that sulphur levels vary in DDGS sources, going back to the particular process the mills are using. “It doesn’t cause the pig as much trouble as it does cattle in their diets, but it is a concern in terms of the environment on how much excretion, especially if you don’t adjust the diet for it.”

DDGS still price into the diet; the value depends on the area where you live, with a higher value for DDGS as a feedstuff in the Upper Midwest.

As producers try to cut costs in their feed bill, Tokach stresses there are trade-offs in saving money but losing production. “There are some negatives. As you add more fiber to a diet, the yield drops, and so you have to take that into account when you’re adding alternative ingredients, especially when you add DDGS that do bring fiber in also.”

Producers interested in mixing up their pig herd rations with alternative feedstuffs need to put pencil to paper, or mouse to computer. Tokach suggests using the KSU economic calculators at ksuswine.org to “estimate the economic value for different phases of grow-finish production, which is where the greater value of DDGS is seen.” In addition to the DDGS calculator, there are other calculators available for producers to perform cost-value comparisons.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like