I fear the reality of the fourth quarter may be tougher than even what the weak markets represented on the CME indicate today.

October 11, 2016

By now, most of you have digested the September Hogs and Pigs report. I will touch on a few items but will not rehash the whole enchilada — and may be in a position of questioning what to do next. I will try to share our thoughts and provide a dusty road map of where we may be going.

A bearish report?

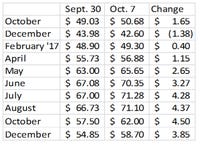

By all objective measures, the Hogs and Pigs report came in above the average analyst guess in nearly every category. That, by itself, is a bearish scenario — but take a look at the attached table that shows the close of futures the day of the report (remember, the report was out after the close so the Sept. 30 values represent pre-report values) compared to values going home on Oct. 7. We have higher values in nearly every contract, except the December where most of the bearish news was harbored.

What does it mean when you get a supportive trade after a bearish report? It would normally mean that the market “knows” something that is overriding the pre-report values. This knife cuts both ways as we have seen bearish reactions to bullish reports in various commodities and you would normally be well-served to heed the trade direction, not the USDA numbers. I am not implying that the USDA numbers are “wrong” at this point — I will offer a critique of the report later — I am simply suggesting that the trade had already incorporated bad news into the market before the report and that these numbers were not shocking enough to send us lower. Yet, at least.

We are up roughly $5 per head since the report with this forward string. Not bad considering the pall we went home with a week ago Friday. A small glimmer I must admit, but better than continuing the trek lower in values.

This general price trend fits in rather nicely to the chart below that indicates the biggest discrepancy in the published numbers versus expectations centered around the December timeframe. The weight breaks are at the bottom of the chart. Note the increased number of animals projected to come to the market compared to last year — the weakness in the December contract is consistent with this data. It will be incumbent on the packer community to continue to run hard through the end of the year to prevent a backup of animals.

Let’s unbundle this one just a little bit to see whether we believe the lack of follow-through to the downside (sans December) is substantiated or fiction.

August export data just came in showing the United States exported 11.4% more pork than we did in August a year ago. This represents a 3.2% increase from July. Not bad, but could be better. The fly in the ointment that prevents things from really getting rolling is the discrepancy between what you are feeling at the farm level and what the importers are seeing for prices.

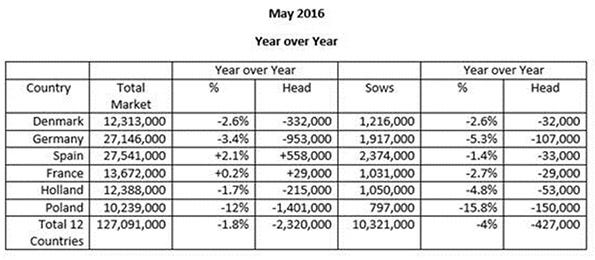

The table below comes from the internet, not exactly the source of all reliable knowledge, and does not reference a source so I am couching my comments given the lack of validation right now. If true, it would indicate that our gains in pig inventories and sow numbers have been countered by losses in the European Union. This would be good news for the U.S. producer as the prospects for importers to turn to our shores would ostensibly improve.

Reasons for my hesitancy to embrace the potentially bullish news.

The recent Successful Farming article indicated the top 35 producers have added more than 120,000 sows year-over-year. I think this is very believable and my conversations with some of the people listed in the publication corroborate the data. How does this data square with the USDA report that shows roughly 35,000 sows added over the same timeframe? Something is awry. I have also chatted with the folks who would be responsible for the sow slaughter — if we added 120,000 and lost 80,000 then the USDA numbers could be believable — who have seen nothing of the such.

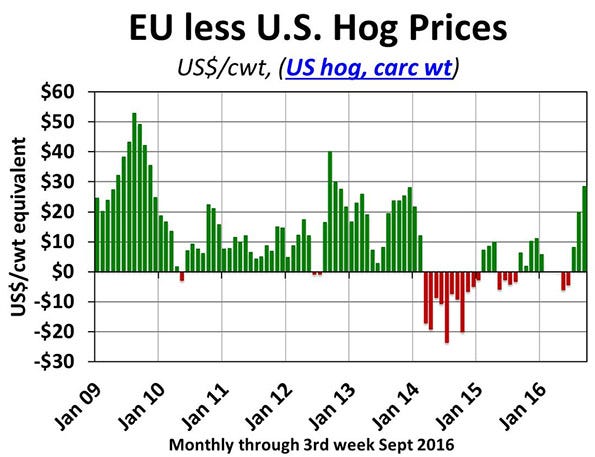

Below are a few charts from my friend Brett Stuart who does an excellent job of keeping abreast of export markets. The first chart represents the spread between the United States and the European Union on a live basis. It is probably reflective of what you already think. With the exception of the porcine epidemic diarrhea era, the United States generally enjoys a competitive advantage (the green bars above the equilibrium line) the vast majority of the time and our recent price compression on the live market side puts us right back in that mix.

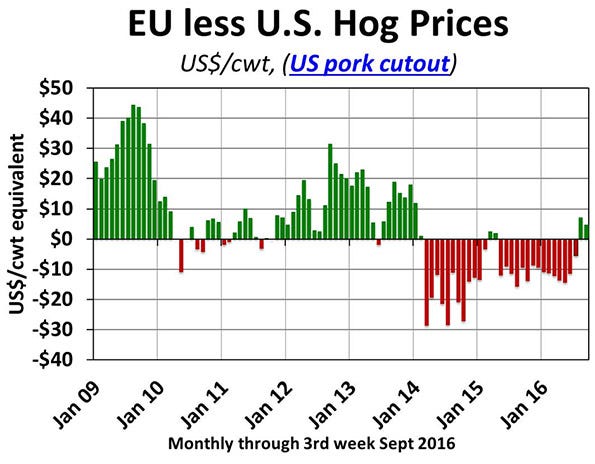

The difference in the cutout value – what an importer would see as a price comparison – tells a different story. The same lack of competitiveness is seen during the PED era; that is no surprise. It is only recently, and by a thin margin, that the United States is again more attractive than the European Union when viewed from this perspective. Packer margins have been handsome and the spread between the live market and the cutout is second only to the disaster year of 1998. Once the United States has forfeited market share to an alternative supplier, it will likely take a sharper price incentive to win back the business.

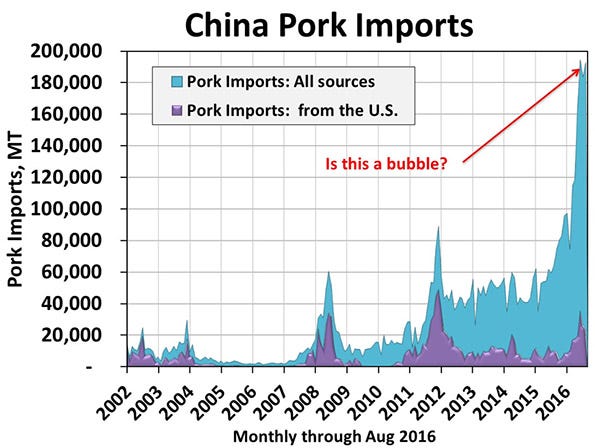

Nowhere is this more evident than in the third graph that depicts Chinese imports and the U.S. share. Note, the promise of China importing pork is real and present. The European Union is taking the lion’s share of the business, in excess of 75%, while the United States remains a bit player. If we want to move the mountain of pork currently on us and on the horizon, the opportunity is present. If we reflect the pricing reality on the farm level to our importing partners, we have a chance to clear the decks.

A silver lining in this revenue compression atmosphere is that the price of corn and soybean meal have remained moderately priced. Our record crops have come at a good time for the pork producer; we could not have stomached high feed prices at the same time of low hog prices. The prospects for a 15 billion bushel corn crop and a 4 billion bushel bean crop will tax storage capacity which should keep basis wide, too.

Bottom line: we are going to experience some tough times in the pork industry. Probably not as bad as 1998 (thank God) and will not have high-priced feed to deal with, but it will likely get worse before it gets better. A peek at the Commitment of Traders report shows we are not well-hedged as an industry; there are still opportunities to keep the winter month economics as a flesh wound. I fear the reality of the fourth quarter may be tougher than even what the weak markets represented on the CME indicate today.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like