Why Vaccines Fail

December 2, 2013

Midwestern grow-finish swine are commonly vaccinated for endemic diseases such as porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2), Mycoplasma hyopneumonia (M. hyo) and Lawsonia intracellularis (ileitis). Vaccinations are not expected to eliminate infections from the herd, but are expected to decrease the severity of clinical disease and associated performance losses.

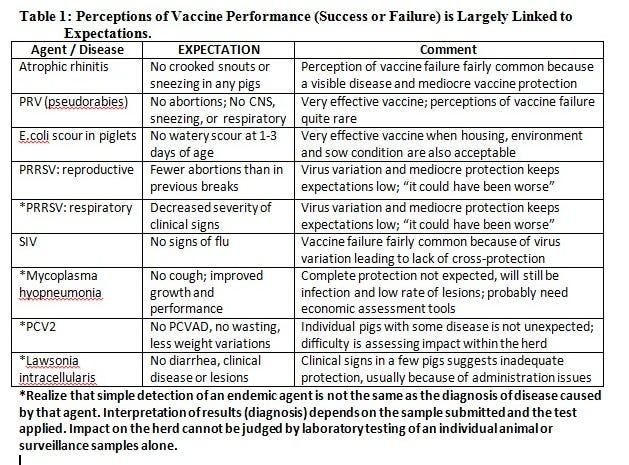

Our expectations for vaccine efficacy vary by the specific disease (see examples in Table 1) and personal experiences.

Consequently, producers or veterinarians occasionally get the sense that a “vaccine is not working” for a particular disease. Does that mean it is a “vaccine failure”? … Or is it a “vaccination failure”?

“Vaccine failure” implies the actual vaccine itself is somehow deficient and unable to stimulate protective immunity. Failures can be because the vaccine is poorly designed or lacks in potency or manufacturing quality. But more likely it is because of strain variations and lack of cross-protection. Examples of variation in efficacy could be vaccines for Streptococcus suis or swine influenza virus.

Like what you’re reading? Subscribe to the National Hog Farmer Weekly Preview newsletter and get the latest news delivered right to your inbox every week!

On the other hand, “vaccination failure” occurs when vaccines are improperly applied or administered. Factors that contribute to reduced efficacy in this case are numerous, often because of human errors of application or judgment. Examples include:

· Timing of vaccination is done for convenience rather than maximum efficacy.

· Ignoring the impact of maternal interference; this can change over time

· Using reduced dose (particularly a risk with killed vaccines)

· Using one dose when two are recommended

· Improper method of vaccination and site of vaccine administration (and some get “missed”)

· Vaccine handling (outdated, poor storage, no refrigeration, poor handling)

· Noncompliance in vaccine administration in not following the label (or even doing the task)

· The health (disease) of animals being vaccinated – In populations of thousands, it is hard to imagine that all pigs are simultaneously immunocompetent. There would be even larger variation in immunocompetence when vaccinating animals that are compromised by diseases (infectious, metabolic or nutritional) or stresses present at the time of vaccination.

· Conclusions based on misuse of diagnostic tests, inappropriate samples, or inappropriate interpretation of highly sensitive diagnostic tests (PCR) – Conclusions based on the use of “surveillance samples” (oral fluids, feces) do not definitively differentiate between infection and disease. Simply put, the detection of an endemic agent is not the same as the diagnosis of a disease caused by that agent.

When vaccine fails to perform as expected, a complete investigation is generally warranted. One recent example is a concern that PCV2 vaccine may not be performing as expected, particularly with the “new variants” or “mutants” reported for PCV2. Two (of many) possible mechanisms for perceived lack of efficacy are that: 1. PCV2 has increased in virulence; or 2. PCV2 has changed immunogenicity such that vaccines are no longer cross-protective.

Researchers can detect differences in PCV2 by sequencing and other techniques, hence a variety of virus types, subtypes, variants and mutants of PCV2 are described. These include PCV1, PCV2, PCV2a, PCV2b, PCV2c and, more recently, a “mutant PCV2b” (mPCV2b).

Despite this diversity of porcine circoviruses (often illustrated by dendograms), recent research studies in the United States have found no evidence to suggest that the changes detected in PCV2 have changed the innate virulence of the virus. Moreover, similar animal studies have found no evidence that current PCV2 vaccines are failing to provide cross-protection.

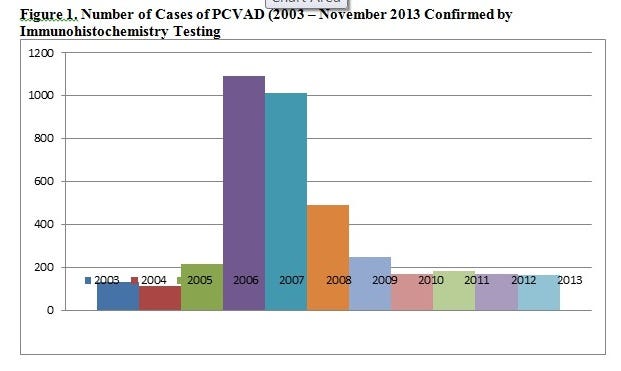

How does that information correlate with diagnostic laboratory data, specifically the frequency of porcine circovirus-associated disease (PCVAD) diagnosis by the Iowa State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory (ISUVDL)? The number of cases of PCVAD has not increased in recent years (Figure 1) despite the increase in the total number of cases presented to the

laboratory.

Neither has the proportion of positive immunohistochemistry tests increased in recent months (Figure 2). Systematic investigations of cases of suspected PCV2 vaccine failure usually confirm either: 1. concurrent infections with other diseases (PRRSV, SIV, M. hyo, PPV); and/or 2. Vaccine compliance issues as listed above.

When a vaccine fails to perform as expected, a careful review and audit of the vaccination process (items bulleted above) are the first steps in the investigation. If additional investigation is warranted, do not underestimate the difficulty in achieving accurate assessment of a disease impact in a population.

Endemic pathogens (e.g. PCV2, M. hyo, Lawsonia) have major differences in their biology, disease mechanisms, diagnostic sampling, diagnostic test interpretations and criteria for assessing economic impact. Seek and use the knowledge and experience of your production team and industry experts (technical service veterinarians, diagnosticians, academics).

Keep the most in-depth pork production information available at your fingertips! Download our Blueprint app today.

You might also like:

Big Producers Make up Pig Losses with Heavier Weights

PED Virus Complicates Margin Management

Developing 11 Findings on Antibiotic Resistance

You May Also Like