From July 8-17 there have been 12 cases of vesicular disease that have been discovered at two slaughter plants in Iowa. All cases have tested negative for FMD and the other swine vesicular diseases, but 75% of them have tested positive for Senecavirus A.

August 1, 2016

Senecavirus A, formerly known as Seneca Valley Virus, has been identified in the U.S. swine population since the late-1980s and has most commonly been associated with “Idiopathic Swine Vesicular Disease.”

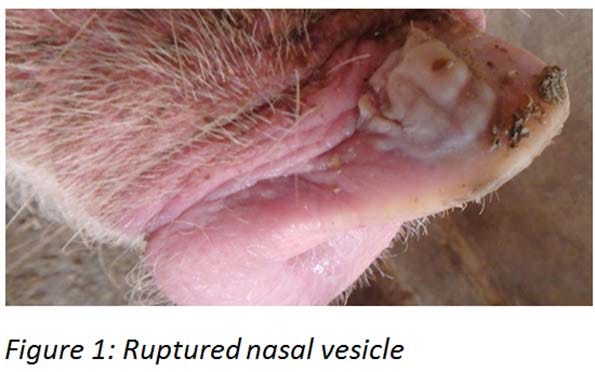

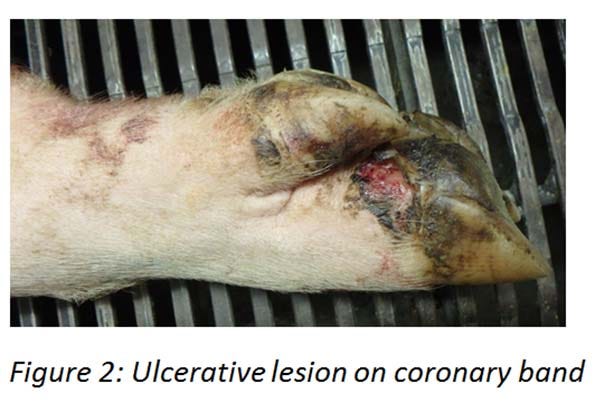

Lesions associated with Senecavirus infection are characterized by vesicle formation and epidermal erosions that progress to ulcers of the coronary band, oral cavity and nasal planum. Gross lesions in pigs are clinically indistinguishable from other vesicular diseases such as foot-and-mouth disease, vesicular stomatitis, swine vesicular disease and vesicular exanthema of swine. Due to the similarity of lesions, foreign animal disease investigations are often initiated in outbreak scenarios to rule out the possibility of foreign animal vesicular diseases.

From July 8-17 there have been 12 cases of vesicular disease that have been discovered at two slaughter plants in Iowa. All cases have tested negative for FMD and the other swine vesicular diseases, but 75% of them have tested positive for Senecavirus A. In all cases, there was no report of seeing clinical lesions at the site at the time of loading the market pigs, but the lesions and/or lameness were discovered during ante-mortem inspection by the USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service veterinarian

Therefore, it is important for veterinarians, pork producers, contract growers and employees to inspect finisher pigs before and during the load-out process. Clinical signs may include the following.

Vesicles (intact or ruptured) on the snout or in the oral mucosa (any muco-cutaneous junction)

Figure 1

May or may not be seen in association with lame pigs

Acute lameness in a group of pigs.

May see ulcerative lesions on or around the hoof wall. (Figure 2)

May see redness or blanching around the coronary bands.

May see eventual sloughing of the hoof wall.

Anorexia, lethargy and/or febrile

In the early course of the disease, fevers up to 105 degrees F have been reported.

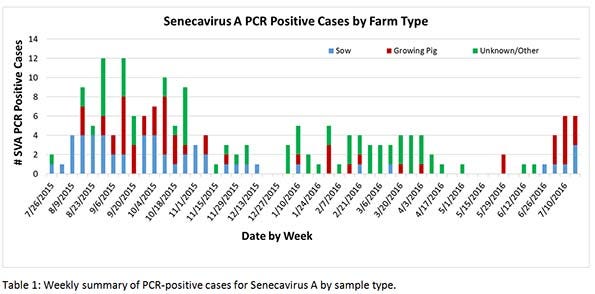

In an effort to quantify the incidence of new cases, Iowa State University began to publish a weekly report of diagnostic case submissions that tested positive for Senecavirus A via PCR (Table 1). Each week, the total number of cases that have at least one positive sample for Senecavirus A on PCR, gets included in the weekly total.

It would be important to note that each positive case would be independent of site, so it is possible that the same site could have submitted cases in the same week or different weeks, and that they could be counted more than once. That case information is then broken out into the “farm type” and also by state of origin, both of which would have needed to be filled in on the submission form. The “farm type” was broken out into sow farms (breeding farms with suckling piglets), growing pig (nursery, finishing or wean-finish) or unknown/other. All of the exhibition swine would have been classified as growing pigs. The state of origin of the site where the case was submitted was the other and from this we can see that most of the cases were from Iowa, but have also seen cases in Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, Minnesota, Nebraska and South Dakota as well.

Table 1 shows the weekly cases of Senecavirus A-PCR positive cases. When the first cases sprung up last summer, we were averaging five to 10 cases per week in August, September and October. The cases waned after that with most positive cases associated with “Other” sample types with a few sporadic sow farm and growing pig cases until the recent uptick in cases over the past three weeks. Almost all of the recent growing pig cases occurred at the packing plant, which demonstrates the reason that producers and caretakers need to be vigilant in inspecting market-age animals during or just prior to the loading process. Senecavirus A is not a new pathogen, but certainly something has changed as we are beginning to see many more cases than what has been seen historically. It is important to remember when vesicular disease is suspected (e.g. lameness, snout and/or coronary bands lesions), the farm veterinarian and state/federal officials should be contacted immediately (before any further pig movements). State and federal officials will determine the next course of action. Because of the similarities of SVA lesions with other foreign animal vesicular diseases, we need to be diligent to test these cases and make sure they are associated with SVA and rule out all foreign animal vesicular diseases.

Senecavirus A is not a new pathogen, but certainly something has changed as we are beginning to see many more cases than what has been seen historically. It is important to remember when vesicular disease is suspected (e.g. lameness, snout and/or coronary bands lesions), the farm veterinarian and state/federal officials should be contacted immediately (before any further pig movements). State and federal officials will determine the next course of action. Because of the similarities of SVA lesions with other foreign animal vesicular diseases, we need to be diligent to test these cases and make sure they are associated with SVA and rule out all foreign animal vesicular diseases.

You May Also Like