The Center for Food Security and Public Health is organized around a mission to thwart bioterrorism scares that may impact the U.S. food supply. The Center is working to increase national preparedness for accidental or intentional introduction of diseases that threaten either food security or public health.

Tucked away in a group of small offices near the diagnostic lab at Iowa State University in Ames is the Center for Food Security and Public Health (CFSPH), headed up by immunologist and distinguished professor James Roth, DVM. He was recruited in 2002 to organize the center to thwart the anthrax and other bioterrorism scares, armed with a three-year grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“The funding came with a mission to increase national preparedness for accidental or intentional introduction of diseases that threaten either food security or public health,” he says.

These days, the thrust, based on annual funding grants from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), is mainly about protecting the nation’s meat, milk and poultry herds and flocks from the threat of foreign animal diseases.

The staff of 30 veterinarians and students, including swine veterinarian Pam Zaabel, is scattered throughout the offices of ISU’s College of Veterinary Medicine, even branching out beyond traditional species. A handbook covers zoonotic diseases of companion animals.

Mutating strains of H1N1 swine influenza virus (SIV) became a zoonotic concern a few years back. In response, the center, along with USDA, the American Association of Swine Veterinarians and the National Pork Board cooperated to produce a brochure for veterinarians on influenza virus surveillance in swine, how the program works and what practitioners can expect after submitting samples. A brochure for on-farm use was mailed to 60,000 producers.

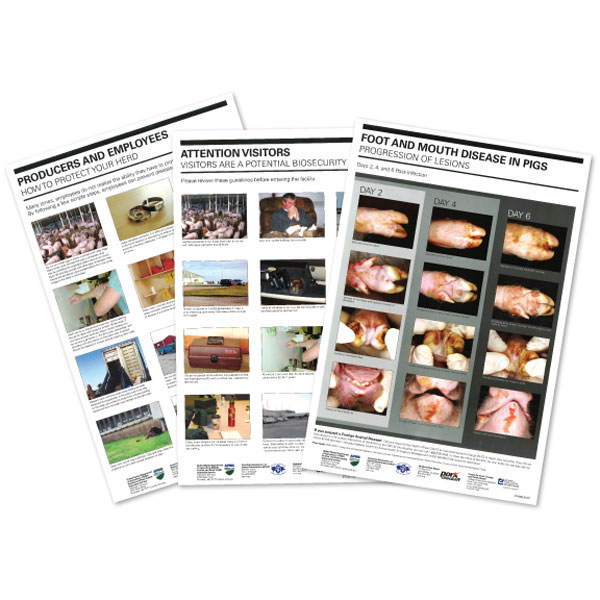

For SIV and foreign animal diseases, the center collaborated with those same organizations to develop a full-color, laminated poster that covers a variety of biosecurity risks posed by visitors to the farm. A related poster depicts how producers and employees can help protect their swine herds from disease introduction by following a few simple steps. Common themes include: do not own or come in contact with other pigs; leave valuables that are difficult to clean at home; stay home if you are sick; wash hands or shower in/out and clean and disinfect hog facilities.

Foreign Animal Disease Focus

Of note, the staff has recently published a book used in a Web-based, one-credit course on foreign animal diseases (FADs).

“USDA funded it because it was concerned that veterinary students weren’t getting consistent, uniform training on FADs. Every vet school teaches it a little differently,” Roth explains. The book is called “Emerging and Exotic Diseases in Animals” because it also covers diseases like bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), which was once a concern of beef cattle in the United States. Technically, it is not a foreign animal disease.

“Now every veterinary college in the United States uses our course and every veterinary student gets one of these books paid for by USDA. And every veterinary student in Canada gets one of these books paid for by the Canadian government,” Roth states. The book is in its fourth printing, and over 20,000 copies have been distributed. It covers the background of causes and consequences of emerging diseases that affect various animal species.

Besides influenza in pigs, it covers diseases that have emerged, such as African swine fever and Nipah virus.

The publication also looks at the human implications when diseased animals cannot be harvested and the food supply is reduced.

In terms of the world’s meat production noted in the book, estimates pegged cattle at the top in 1961, but by 2007 pork had bypassed both cattle and poultry in terms of tons of meat produced for human consumption, Roth says.

Details on the book are featured on the center’s Web site, www.cfsph.iastate.edu. The site records an amazing two million hits a month, about 60% from foreign countries and 40% from the United States, he estimates.

With USDA funding, the illustrated text has now been translated into Spanish and is being made available in Central and South America. Guatemala, in Central America, is now in the throes of a classical swine fever outbreak. “If we can help them control the diseases in their country, then the diseases are less likely to come here,” Roth says.

FMD Focus

The elephant in the room when it comes to foreign animal diseases is foot-and-mouth disease (FMD).

“We had FMD in the United States in 1929; western Canada had it in the 1950s,” Roth recalls. “Back then, animals didn’t move like they do now. The Pork Board has estimated that every day there are 625,000 pigs on the road in trucks just in the United States. If the FMD virus starts from pigs born in North Carolina, for instance, it may come here (Iowa), which is why we are really trying to help get ready,” he emphasizes.

Roth says the drop in hog prices in 2009, due to the pandemic influenza outbreak, was just a minor blip compared to what would happen if FMD struck U.S. livestock operations. With any of a group of foreign animal diseases, FMD being the worst, the United States would immediately lose its export markets. That would be especially crippling for the pork industry, which ships 27% of its production out of the country. Estimates are that hog prices would drop $50-60/cwt. immediately and the agricultural economy would suffer billions of dollars of losses.

If FMD were to get into feral swine, it would be even tougher to control and more difficult to identify in wild pigs due to their darker appearance, says Pam Zaabel, former director of swine health information and research for the National Pork Board.

To help veterinarians distinguish whether vesicular lesions are FMD, USDA, in working with the center, the National Pork Board and the AASV, mailed out pocket guides showing the sequence of FMD lesions, which are important to appropriate control measures, Roth says. A wall-mounted poster was created by the center and printed by the Pork Board to hang in production units to illustrate the progression of FMD from Day 2 to Day 6 post-infection. The FMD pocket guide and the laminated posters (pictured above) are available to pork producers free of charge from the Pork Store at www.pork.org.

Swine Projects

A preliminary project drafted early last fall, the Secure Pork Supply, is modeled after the Secure Egg Supply project developed over the past five years and a more recent Secure Milk Supply project.

As with egg farms, if a foreign animal disease infected a hog farm, a quarantine zone of at least six miles would be placed around the infected premise. All movement would be stopped within that control zone and animals would be tested for infection, Roth says. Then the huge effort of tracking the diseased animals back to their origin would begin in an effort to determine how the disease spread.

“That is why the National Pork Board has been pushing so much for animal traceability in the United States,” Zaabel says. Without a national identification program, traceback will be very difficult, Roth adds.

“We are trying to come up with the science that says in the case of FMD, for instance, there is low risk if you move your milk, and the same science applies if you move your pigs,” he continues. Unlike milk, pigs don’t have to be moved every day, but you can’t wait very many days when pigs need to be weaned or moved to a finisher, Zaabel says.

Roth declares: “One of the reasons that we are so vulnerable to FMD is because we are so efficient at food production; pigs, as with milk, depend on just-in-time movement to be efficient.”

That’s given the Iowa State center a huge charge — to come up with ways to safely keep things moving or get things moving again — in the face of a foreign animal disease outbreak.

Lessons Learned

Roth believes global experience offers guidance that will help ensure the success of the Secure Pork Supply plan. For the FMD outbreak in the United Kingdom in 2001, the plan was to stop all movement and kill everything that was infected or in contact with infected animals. Animals were mostly burned.

Then about a year ago, FMD struck South Korea, and they took the same approach, killing and burying livestock. Officials ended up killing a third of the pigs and then vaccinating because they couldn’t overcome the disease. Burying has caused groundwater contamination issues.

USDA is working with the center and food animal production industries to change eradication philosophy. A small FMD outbreak would still be stamped out. But larger breaks of FMD would rely more on vaccination to bring the disease under control, Roth explains.

Two concerns regarding FMD vaccination are adequate vaccine supply and how to detect whether vaccinates are healthy or perhaps carrying the disease.

Roth and Zaabel have developed a broad outline for the Secure Pork Supply plan reviewed by a 50-member advisory committee comprised of government and pork industry representatives. Overall, the committee is charged with developing biosecurity performance standards for all phases of production, transportation and processing to protect all phases from FMD.

Roth admits this voluntary system will take years to develop and implement to provide a high degree of assurance that if the swine industry gets FMD, it can be contained.

One day, it may be possible to develop FMD-free production systems, called compartments, within infected countries. If these compartments remained negative for disease, they would be permitted to continue exporting.

“Nobody in the world has ever done it, and it is not an easy thing to do, but we are going to study the economic feasibility of developing compartments and getting USDA and trading partners to recognize them,” Roth says.

Learn about the food security threat posed by feral swine in the related article, "Feral Swine Surveillance Focuses on Classical Swine Fever."

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like