When The Maschhoffs was approached by processors about raising ‘no antibiotics ever’ pork, the company’s leadership listened and started to do its homework.

Growth can make or break a business. Increasing revenue is not about running at your competitors’ pace, but rather building a well-calculated plan that is adaptable to changing markets and practical for your operation.

As the pork industry lurches into an unprecedented growth mode, lessons can be learned from business leaders who have successfully executed plans that help the companies like The Maschhoffs reach new heights.

Over the past decade, The Maschhoffs has increased revenue 15-fold, but not by accident. The Maschhoffs’ executive team had the foresight to know the key to sustainable growth is strategic prioritization, and a firm understanding that opportunities are infinite and resources are finite.

For the company, moving forward sustainably means reflecting on the past and staying true to core values, but thinking differently about the future. Bradley Wolter, The Maschhoffs president, shared at the recent Allen D. Leman conference that the company is at a crossroads.

“We continue to recognize that cost of production is absolutely core to remain competitive. At the same time, we continue to hear more and more interest from a consuming public in our operations. Consumers want to know where their food comes from, and they have an increasing number of expectations for the entire food supply chain,” explained Wolter. “Looking forward, we must determine how to align with these expectations as they relate to consumer values in terms of how animals are produced.”

Like most progressive companies, The Maschhoffs understands advancing in the future is necessary, and the next logical transition points to a value-added era. However, defining the value-added transition for the company may not be simple, especially with consumers’ expectations in a continuous state of flux, but it indeed sparks inspiration for value-driven innovation.

Chicken business education

When pork processors approached The Maschhoffs about raising “no antibiotics ever” (NAE) pork, the company’s leadership did not turn a deaf ear. After all, closing the mind to new opportunities without doing the homework can only place limits on the growth of business. And this is not the first time. The Maschhoffs had also considered an atypical opportunity when it entered the chicken business in 2013 with the purchase of GNP Co.

Diversifying the company’s profile to a multi-protein focus creates the opportunity for synergy by utilizing lessons from the chicken business and gaining fresh perspective on consumer demographics and shifts in food trends. Julie Berling, senior director of strategic insights and communications for GNP Co. and its sister pork company, says the meat protein business is facing hard realities as the millennials will have more spending money than any other group by 2017. This age group doesn’t require meat as their main protein and makes food buying decisions based on core values. She says, “If you do not stay relevant to that millennial audience, you could quickly lose. It creates hard realities for meat proteins.”

Berling, a 21-year veteran of the poultry business, experienced firsthand the path to chicken raised without antibiotics. In 2004, GNP Co. began noticing some early indicators that consumer interest in antibiotic-free meat was on the rise as it started to see a new higher standard of natural that included the “no antibiotics ever” attribute emerge in the market. As a result, the company saw its premium quality position and market share begin to erode.

The Gold’n Plump brand fell into the middle by not being the cheapest chicken, but not providing value-added attributes such as antibiotic-free or certified humanely raised. The middle ground was not a desirable location. So, GNP Co. was driven to pursue NAE poultry production. Since it was unreasonable to shift all the company’s entire production to an NAE production model overnight, GNP launched a new brand — Just BARE. Given that Just BARE chicken was not the first NAE chicken to the market, the company offers other value-added attributes, including vegetable- and grain-fed, an all-clear recyclable tray, and traceable farm code, to set it apart from the competition.

Watching the activity in fast foods and restaurants is helpful when predicting future retail food trends, Berling says. “We typically see trends emerging in the fast-casual segment. When you see trends gaining momentum, you know they are going to hit the retail shelf within five years.”

Today, 100% of the company’s flocks in Minnesota are NAE, as are 20% of the flocks in Wisconsin. Recognizing a further shift in the poultry consumer, GNP Co. sees a shift of NAE from a niche market to mainstream. Consequently, the company set a goal for all the company’s flocks to be NAE by 2019.

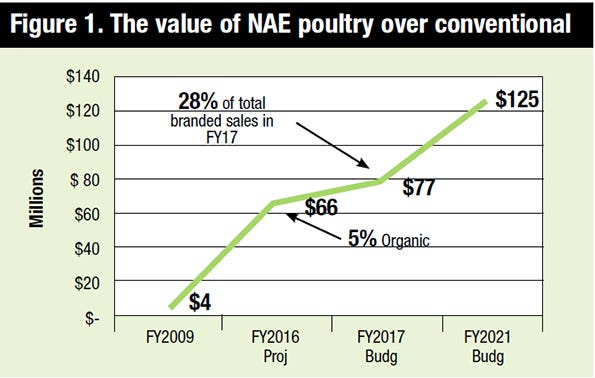

For GNP, the NAE value has grown Just BARE brand revenue by double-digits year-over-year; and the company estimates sales in 2017 to account for 28% of the chicken company’s total branded sales (see Figure 1).

Berling acknowledges that value-added attributes — NAE, vegetable- and grain-fed and humane certification — contribute to additional production costs. Overall, the company estimates these attributes cost 10% more. It also causes an increase in feed costs, a slight decline in bird performance, an increase in sanitation requirements, lower efficiency due to reduced barn density, heightened biosecurity and slightly less bird uniformity.

Therefore, the real challenge for NAE chicken is selling the entire bird for a premium to offset the 10% increase in production cost. The company earns a premium for Just BARE boneless skinless breasts over conventional boneless, skinless products; however, pricing is competitive with similar products. Receiving that premium is much more difficult for the dark meat.

For now, the company can switch a barn over to conventional production if a disease outbreak would occur, but that will not be possible once the production model is shifted to 100% NAE across all its flocks. Hence, the big question is, is 100% NAE chicken production sustainable long-term.

Berling says, “Our company believes it is. The challenge is that everything has to go right with NAE production for it to work efficiently. Good husbandry; constant monitoring; and new advances with probiotics, feed and vaccines are critical to our ability to sustain NAE.”

Applying economics

Building on that knowledge from its poultry side, The Maschhoffs began investigating NAE pork production from an innovation point of view. At this point, the company has not produced any marketable NAE pork, explains Aaron Gaines, vice president of technical resources and support operations at The Maschhoffs. “After receiving the first customer call on producing NAE pork, the first thing that comes to mind is what we are going to get paid for that type of program,” Gaines says. “From there, the team started the internal diligence process to understand the potential cost of raising NAE pork and understanding our business realities to sustain such a program.”

Truthfully investigating the business reality begins with asking several questions beyond the premium offered by the packer. One large hurdle for the swine business is the increase of prevalence of endemic and epidemic disease challenges. The Maschhoffs is currently spread across nine states, many of which would be considered hog-dense areas. Overall, the company, similar to fellow pork producers, is encountering herd health destabilization and facing new epidemic disease outbreaks in the past few years. Furthermore, the rapid growth of the company’s asset base has resulted in commingled pig flows. Combine those animal health challenges with an industry change in antibiotic use due to the new Food and Drug Administration guidance coming online in 2017, and it creates an unfavorable environment for efficient NAE production. Gaines says, “The other question is how big is this runway for producing NAE pork in gaining that premium in the marketplace, particularly when you consider what has happened in poultry.”

Further, he stresses, “As we look at some lessons learned from our friends on the poultry side, the question is how we maintain the high level of animal care. So the intensity of animal management is going to have to increase with these types of specialty programs.”

Truthfully, it all comes down to economics. Once the premium is proposed, it is necessary to determine the cost of production, along with the workability for the operation.

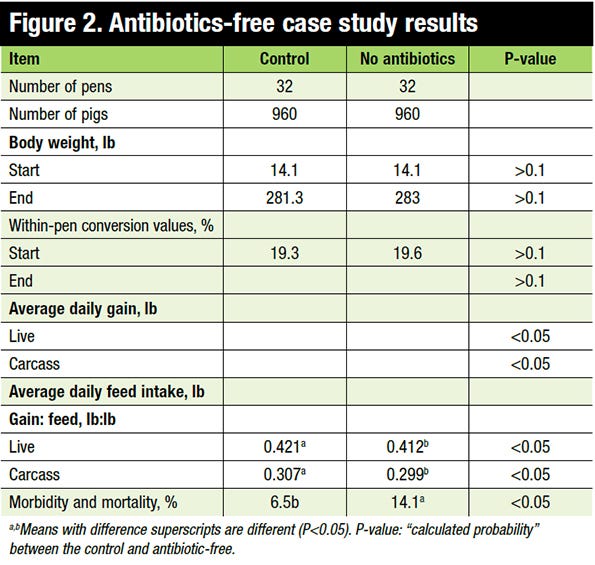

Gaines and his team began the NAE case study by looking at the difference in performance of pigs raised with antibiotics versus pigs raised without antibiotics under the current production model. Unlike a typical NAE program, The Maschhoffs treated sows and piglets with antibiotics in the prewean stage as part of this preliminary research project. Still, the trial gave the company a real-life comparison into the cost implications.

The trial was held June through November in 2014. All piglets were given an antibiotic at processing, and antibiotics were used therapeutically for all sows and piglets during lactation. Thirty-two pens with 30 pigs each were raised with the company’s current practices, and 32 pens with 30 pigs each were raised without antibiotics from wean to slaughter. All pigs were vaccinated for porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome three weeks post-weaning and tested positive for swine influenza virus and Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae.

As result of the research, the team found the cost of production for NAE pork was 14% to 21% higher than conventional production with an increase in pre- and post-weaning mortality (almost double) being the biggest economic driver (refer to Figure 2 for complete results).

Also, an NAE production model is more labor-intensive and requires experienced caretakers when animals are challenged with health stressors. Care standards have to be at the highest level because stress must be minimal, and the pigs cannot be put in a situation to take on any serious health issue. Gaines says, “Even an experienced caretaker will have to learn this new production practice to be successful and consistent. Everything has to go right along the supply chain.”

The next step in the discovery stage is to evaluate how to optimize the NAE production system to improve profit margins. Nutrition, health, genetics and housing are all key fundamentals.

“These programs are not going to be strictly sorted out by the nutritionist and veterinarian,” Gaines warns. “It is going to be a multifaceted approach across the business to solve how to launch an NAE program that is sustainable from a cost of production standpoint and profitability.”

Several problems arise from a nutrition perspective. A tricky situation is handling antibiotic-free feed rations and eliminating cross-contamination at the feed mill that handles feed diets for multiple programs. Gaines says, “We challenge the nutritionists to really design feed programs that reduce the number of diets for phase feeding and offset some of the extra costs at the feed mill due to changeovers.”

There is no magic bullet or perfect alternative feed additive that can completely replace antibiotics. The second challenge for the nutritionist is identifying feed additives and ingredients that improve pig health. Finally, the nutritionist needs to leverage antibiotic alternatives to counterbalance the impact of NAE on pig growth and feed conversion.

Turning to the health experts, it will be necessary to identify the source of pig flows best suited for NAE pork production, which likely means a shift away from the commingling of pigs. Furthermore, Gaines explains the following adjustments need to be made to the production model.

■ An increase in diagnostic testing to manage disease risk for given source flows

■ Implementation of more advanced biosecurity programs or technologies to manage epidemic disease risk

■ Reduction or elimination of disease pressure associated with endemic disease by leveraging new or existing health product technologies

From a genetic perspective, it will be necessary to determine the optimal genetic lines for NAE production, especially pinpointing the individual sires with low progeny total mortality. The goal is to produce robust piglets that can handle animal health threats without antimicrobials.

Housing requirements for NAE production can create problems. As discussed with NAE chicken production, stocking density reduction is an issue. “Mortality and morbidity rates tend to increase at floor spaces below 6 square feet. The question is, will that response be different for NAE production. From what we know from poultry, it certainly looks like you have to reduce stocking rates to reduce stress on the animal,” says Gaines.

Also, the barn needs to be redesigned to facilitate animal care practices associated with NAE pork production. The goal is to make it easier for the pig caretaker with intense management required by the system.

Presently, Gaines confirms there is no way to produce NAE pork without an increased cost in production. In the future, it will take new technologies that can actually replace antibiotics. He says, “We are a long way from that. If you look at the history of antibiotic development, it is not something that happened in a five-year period.”

Ultimately, it will come down to if the consumers are willing to pay more for pork raised without antibiotics long-term on a large scale. From there, Gaines says, “It will take the best growers, best nutrition and the best of everything to run an efficient and successful NAE program. Everything has to go right with this type of program.”

At this point, The Maschhoffs is just in the research stage. The company sees NAE pork production as a potential fit in the company’s overall production model, but on a small scale as a portion of its already diverse portfolio. Gaines says, “If we look at an NAE program in the future, we’d certainly do a pilot project on a small scale to understand the actual cost of these programs. We certainly would not blanket it across the whole system. We would be strategic.”

Despite the final decision to participate in an NAE program, Gaines warns the industry must be careful. “The industry must maintain high standards of animal care with this type of program. You can’t sacrifice animal well-being at the expense of implementing an NAE program. There is a balance the industry needs to be conscious of as they look at this program. It certainly appears to have its challenges.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like